Unmasking Georgian Class Structure: Summary of a New Study

I’m committed to sharing knowledge—research, summaries, translations, and on-the-ground insights. If this independent media matters to you: Become a paid supporter (if you have the means)!

There's nothing I love more than a class composition study – they're incredibly difficult to do yet vitally needed. This work, 'Class Structure in Georgia' by Kote Eristavi and Ana Mikhelidze, maps Georgia’s class composition to expose our real problems beyond superficial political agendas. I deeply welcome this ambitious effort; knowing how painstaking such research is—especially in Georgia, where hostility to class discourse stifles dialogue and resources for such work scarcely exist.

I won't focus on gaps (the authors surely recognize future needs). Below is my summary of their findings—unless noted, these are condensed study points, not my commentary. The Georgian original is available here.

Class Structure in Georgia Study

Why Class Analysis and Background to Georgia

The authors argue class analysis exposes hidden structures of domination and exploitation—from state policies (e.g., Georgia's class-biased criminal justice) to ideological narratives—revealing how class positions shape lives, inequalities, and political potential, while empowering strategic solidarity against systemic injustice.

While sociology offers distinct class models (Weber's life chances, Bourdieu's tripartite capital, Marx's property-based exploitation), the authors adopt Wright's neo-Marxist framework—prioritizing oppression/liberation analysis—to map Georgian class conflicts and alliances, without dismissing complementary insights from other traditions.

The authors use Wright’s framework to expand Marxist class analysis beyond property relations by adding authority (control over others' work) and autonomy (control over one's labor process), revealing three contradictory class locations that occupy antagonistic positions between primary classes.

According to the authors, independent Georgia's class structure emerged from Soviet collapse and IMF/World Bank-mandated neoliberal "shock therapy" (1992–1994), featuring mass privatization, state dismantling, and austerity. These reforms—implemented amid civil war and hyperinflation—triggered catastrophic deindustrialization: industrial employment plummeted from 695,000 (1990) to 284,000 (1996), with total production collapsing 78% by 1995 and formal sector jobs evaporating. The destruction of stable, skilled employment created a permanent underclass while consolidating power among oligarchic capital aligned with foreign financial interests.

The authors note that Georgia's 51% unemployment surge in the 1990s reflected mass displacement into subsistence agriculture and informal work—which comprised 52% of employment by 1999. Concurrent state collapse dismantled social safety nets through pension arrears, gutted worker protections, and confiscation of Soviet-era union assets. These forces, combined with skilled workers embracing neoliberal "meritocracy" over solidarity, catastrophically weakened collective labor power during transition.

According to the authors, Georgia's post-Soviet collapse triggered a mass shift into small-scale farming and a ballooning "surplus population" (unemployed/underemployed/precarious workers), while deindustrialization dismantled skilled labor and social protections—catastrophically impoverishing most citizens. Simultaneously, a politically connected capitalist class emerged through predatory asset grabs rather than productive investment, creating extreme inequality and fragmenting into rival oligarchic factions that would later drive the 2003 regime change.

The authors argue that post-2000s Georgia intensified neoliberal reforms—accelerating privatization, deregulation, and public sector cuts—to attract foreign investment through employer-friendly policies like wage suppression and anti-union measures, culminating in the 2011 Freedom Act that constitutionally restricted taxes and social spending. This, they say, cemented an extractive economic model: manufacturing stagnates at 9.3% of GDP while low-productivity tourism/retail dominates, trapping rural populations in subsistence farming (6% GDP share despite high employment) and workers in precarious, disempowered conditions.

They clarify their class terminology as follows:

Small Employers

Wright considers small employers to be those with fewer than 10 employees. His criterion is conditional, as he does not have access to data that would accurately measure the amount of capital and the involvement of employers in the work process. Such data is not available to the authors either, and therefore, at this stage, they use Wright's criterion.

Self-Employed (petty bourgeoisie) [note: I disagree with categorizing self-employed without any workers as petty bourgeoisie]

For the purposes of the authors’ typology, they refer to the self-employed category as people who 1) engage in economic activity, 2) own the means of production, but 3) do not have hired workers (unlike the Geostat methodology, where self-employed people may have hired workers), and 4) are not involved in agriculture (they include self-employed people involved in agriculture in the class position of small farmers).

The authors define genuine self-employed (petty bourgeoisie) as non-agricultural, workerless owners free from exploitation, but labor surveys fail to distinguish them from dependent self-employed—workers tied to 1–2 clients via service contracts who lack autonomy over work conditions. These workers (e.g., 22,794+ Georgian taxi/delivery drivers under algorithmic control, construction laborers, and salon "renters") are reclassified by the authors as semi-independent workers due to experiencing domination, exposing how "self-employment" masks exploitation in Georgia’s informal economy.

Managers and Supervisors

Managers are identified using Geostat’s ISCO-08 occupational groups, while supervisors are defined as non-managerial employees who report supervising others in labor surveys—including professionals reclassified as non-professionals if they oversee staff. This approach captures critical nuances (e.g., top managers acting as de facto owners/shareholders vs. low-level supervisors functioning as order-relayers with minimal autonomy), but the authors note that future research must refine authority gradients to accurately map class positions.

Semi-independent workers

Semi-independent workers are provisionally defined by the authors as hired professionals (per ISCO/Labor Force Survey) who lack supervisory roles, leveraging specialized knowledge/skills to mitigate workplace domination and exploitation. However, this category requires refinement—not all professionals have meaningful autonomy (e.g., junior roles), while some non-professionals (e.g., skilled technicians) may control their work process, highlighting the need for empirical research on actual job independence in Georgia.

Small Farmers

Georgia’s small farmers (subsistence/market-oriented agriculturists) represent a distinct class position absent in Wright’s Western-centric model, defined by vulnerability to land dispossession and reliance on fragmented wage labor alongside precarious self-employment. Unlike prosperous Western landowners, the authors argue they occupy a semi-proletarianized "contradictory class position" due to high client dependency (often resembling disguised employment) and seasonal proletarianization. This periphery-specific reality necessitates re-theorizing their place in capitalist class structures through empirical study of their hybrid livelihoods.

Dynamics of class structure development

Long-term analysis of Georgia's class structure dynamics is severely limited, according to the authors, by unavailable early-2000s labor data and incompatible pre-2020 surveys (2009/2017), restricting comparative analysis to only the 2020 and 2024 Labour Force Surveys. Technical and methodological discontinuities prevent reliable historical tracking, confining this study's temporal scope to a narrow post-2020 timeframe despite the recognized importance of observing structural shifts across decades.

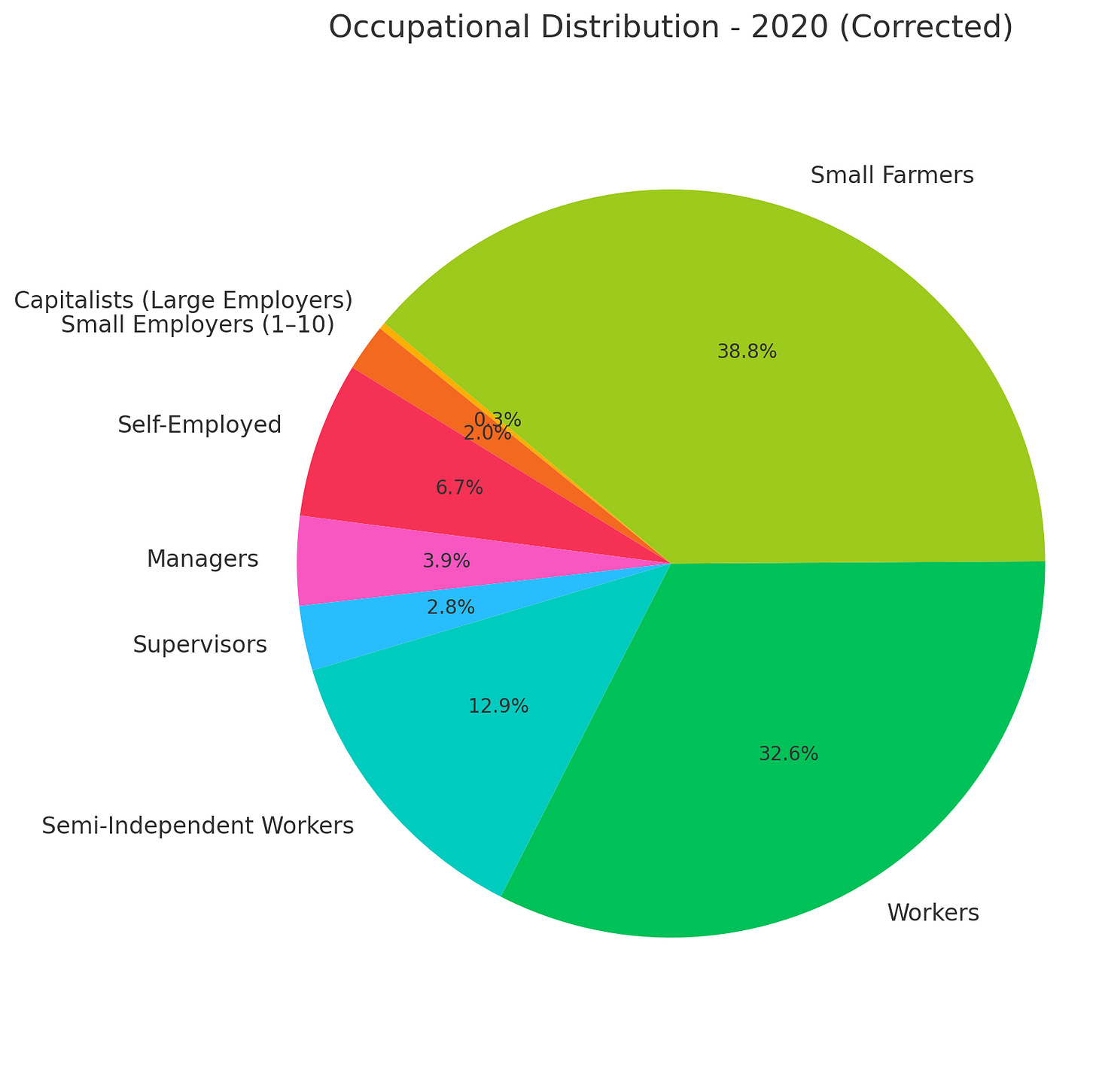

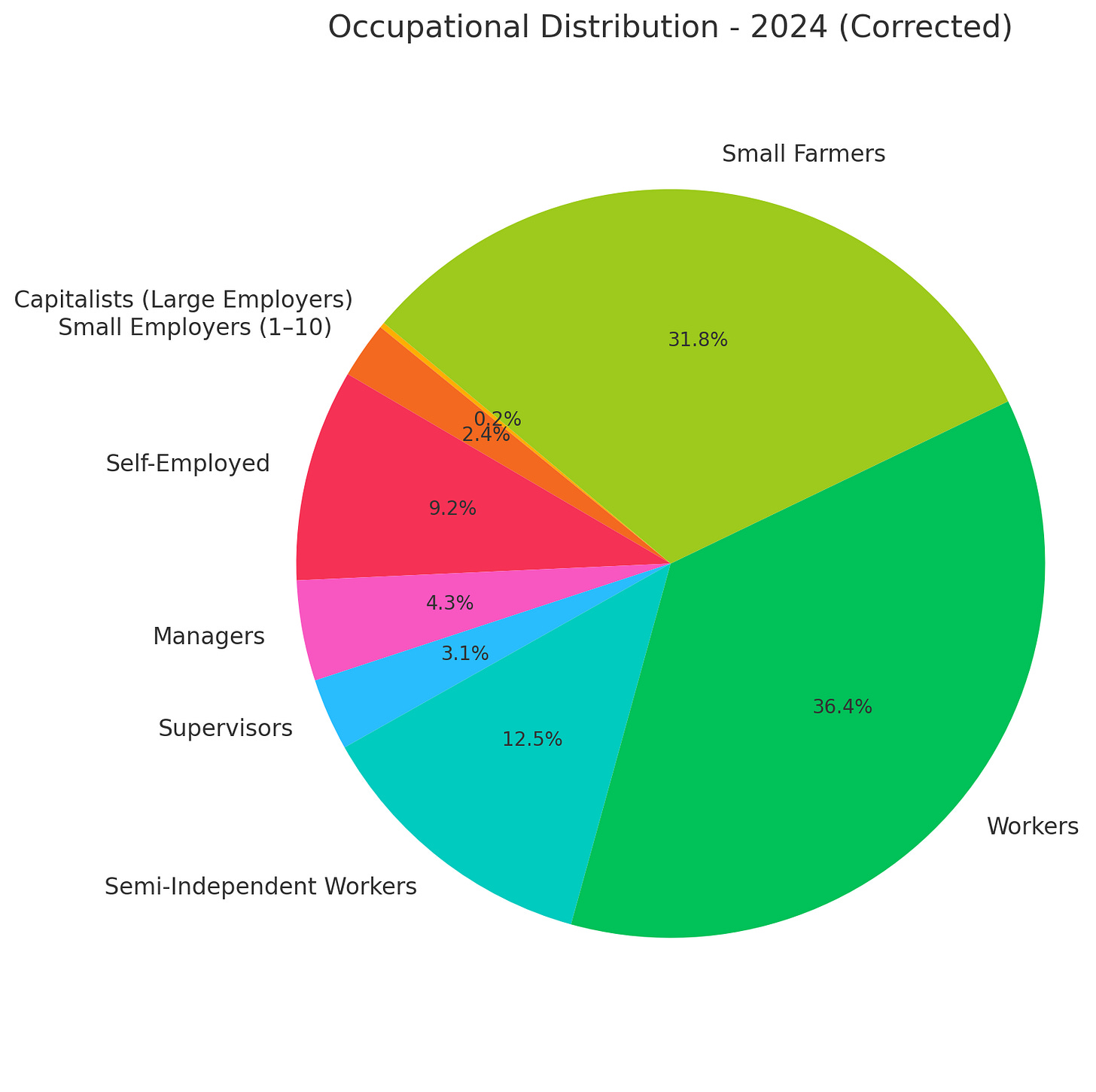

Georgia’s class structure is divided like this: Class of capitalists (not involved in the production process); Small employers (involved in the production process); Class of self-employed (urban employment. excluding dependent self-employed); Managers (excluding top managers, who are practically no different from employers); Supervisors (in case of real control over the planning and/or implementation of the work process); Semi-independent workers (in the case of substantial control over the planning and implementation of the work process); The working class; Small farmers.

Georgian Language Table from Study.

Total (Employees+those working in subsistence agriculture) 1,689,159 in 2020 and 1,772,583 in 2024.

Capitalists (Large Employers): 2020:4,965 2024:4,068

Small employers (1-10): 2020:34,111 2024:42,422

Self-Employed: 2020: 112,680 2024: 159,658

Managers: 2020: 64,631. 2024: 75,689

Supervisors: 2020: 46,844. 2024: 54,260

Semi-independent workers: 2020: 215,436. 2024: 218,490

Workers: 2020: 546,034 2024: 634,780

Small farmers: 2020: 649,407 2024: 553,400

(My own generated AI diagrams)

According to the authors, Georgia's peripheral economy features an undersized working class and scarce managers due to deindustrialization, while its large semi-independent professional class (58% state-employed) reflects an outsized public sector. High self-employment (fueled by tourism/tax incentives) and widespread small farming emerge as survival strategies amid weak social protections and semi-proletarianization.

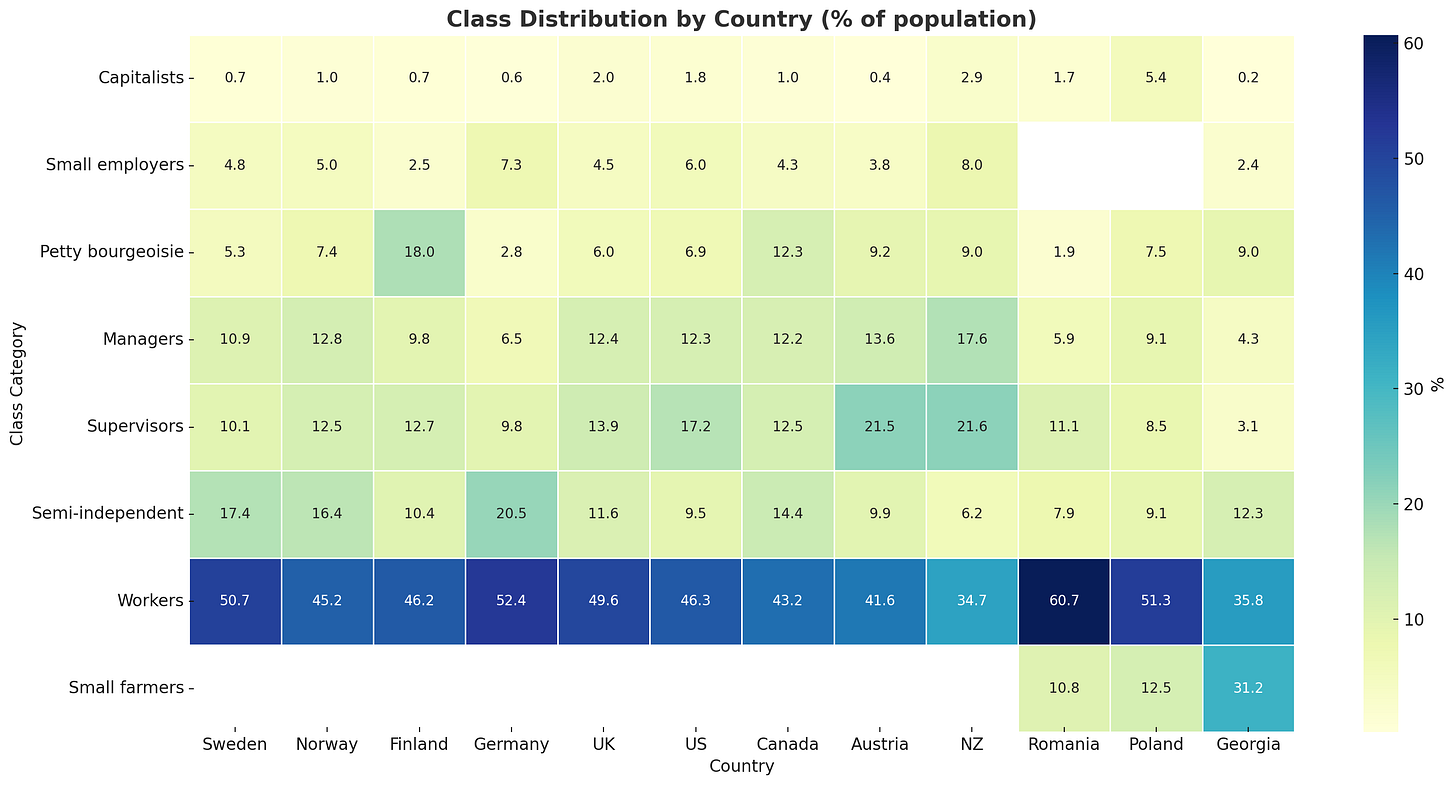

This chart below shows the class composition of developed countries, note the category of small farmers.

Chart was translated by me and made by AI using the Georgian language chart in the study.

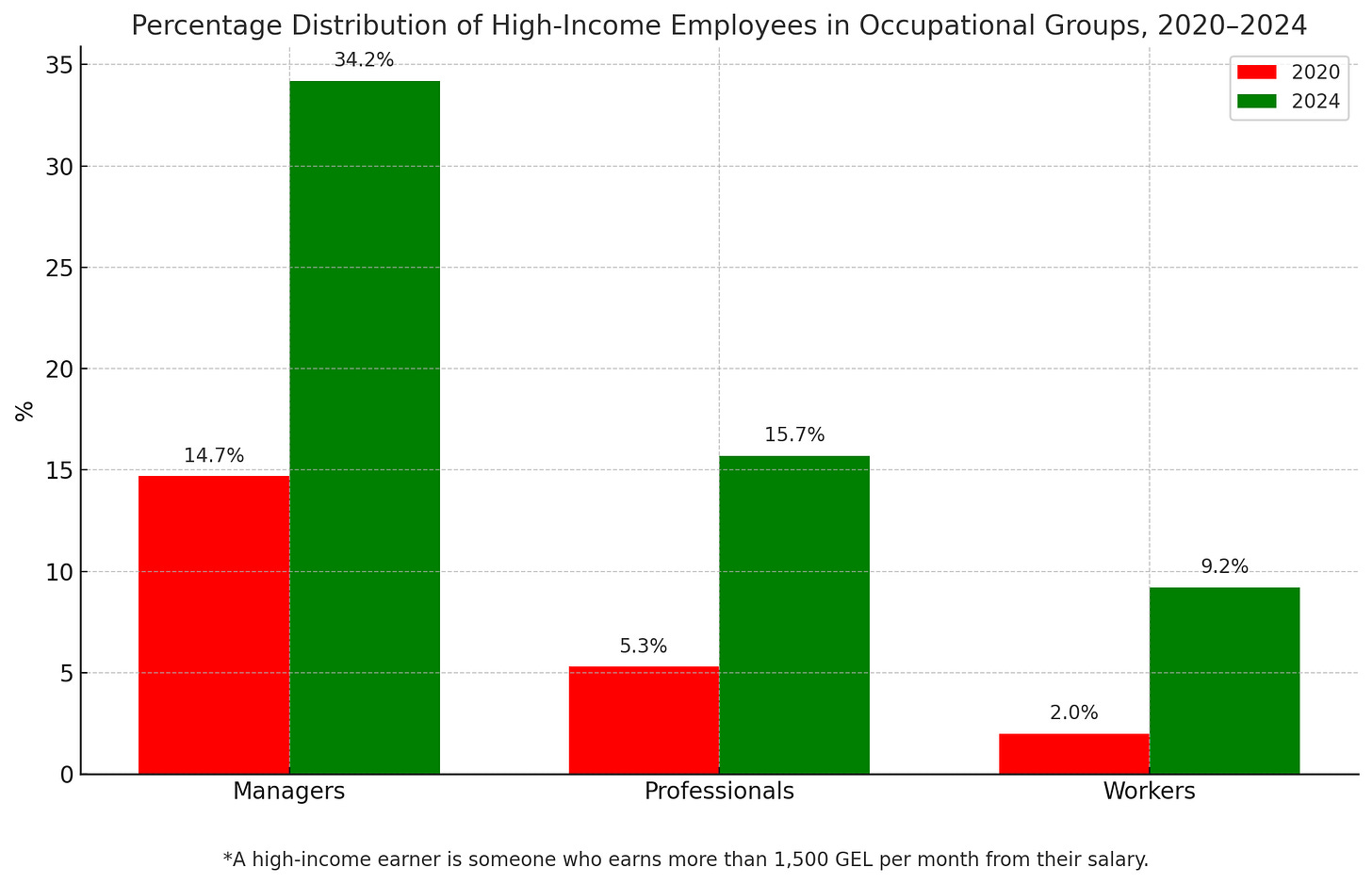

While wage differences between job positions are often deemed legitimate (unlike discriminatory intra-position gaps), Georgia's 2020–2024 data, as interpreted by the authors, reveals these disparities reflect power imbalances—not merit—as managerial wages surged 20% versus just 7% for workers, outpacing employment growth. This widening gap, driven by weak unions and regressive policies, fractures worker solidarity and aligns privileged employees with capital interests—contrasting sharply with egalitarian models like postwar Sweden’s union-driven solidaristic wage system.

Translated graph from study

The authors observe that Georgia's Soviet legacy created widespread high education (to this day, nearly 1/3 of low/medium-skilled workers hold degrees, including 15–17% with master's), yet this human capital is severely underutilized in its deindustrialized economy—revealing systemic labor market failure. Future research, they argue, must analyze how class positions perpetuate inequality, enable (or block) social mobility, and shape attitudes toward economic organization and capital-labor relations.

Other Important Issues in Class Analysis

Precarity

While Guy Standing's concept of the "precariat" identifies precarious work as defining a new class in modern capitalism, the authors argue that in Georgia, job vulnerability permeates all classes—from managers to self-employed workers—making employment instability insufficient for class distinction. They contend precariousness is a universal condition in Georgia's economy that requires empirical study of its varying intensity within and between existing class positions, rather than constituting a standalone class.

Secondary Exploitation

While primary exploitation occurs through employer-employee relations during production (e.g., wage suppression), secondary exploitation operates via exchange mechanisms (Lapavitsas 2013)—where capital appropriates income through rent, interest, or fees, targeting wages, aid, or self-employment earnings. In Georgia, the authors argue, workers face dual exploitation: exploited first by employers and again as tenants/borrowers. Meanwhile, ostensibly "independent" self-employed market vendors (e.g., stall holders) escape primary exploitation but endure secondary exploitation via punitive stall rents/fees imposed by market owners. This secondary layer proves especially acute for Georgia’s surplus population—those excluded from formal labor and reliant on fragmented incomes vulnerable to financial extraction.

Surplus Population

The "surplus population"—groups superfluous to immediate production needs (e.g., unemployed, pensioners, students)—remains integral to capitalism, according to the authors, through financial exploitation (e.g., Liberty Bank’s predatory pension loans) and its role as a disciplining reserve army of labor that suppresses wages and awaits mobilization, as seen historically with Western women’s entry into the workforce or neoliberal reliance on Global South labor. In Georgia’s peripheral economy, this population is exceptionally large and subjected to heightened state control as a "destabilization risk," while its reproduction systematically undermines worker power through precarization and debt traps.

World Systems and Class Structure

World-systems theory (Frank, Wallerstein) posits that the Global North enriches itself at the expense of the Global South through structural mechanisms like debt regimes, extractive trade policies, and institutions (IMF/WB/WTO), confining peripheral economies like Georgia to roles as raw material suppliers and cheap labor reservoirs. The authors argue that this position in the global hierarchy fundamentally molds national class structures—yet Georgia’s specific patterns of dependency remain critically understudied and demand urgent research focus.

Conclusion

This study maps Georgia’s class structure to expose deep-rooted inequality driven by class oppression, identifies critical research gaps (e.g., surplus populations, global dependency), and argues that centering class conflict is essential—both to understand societal crises and to mobilize for justice beyond superficial cultural/geopolitical debates.

The self-employed owner-operator is most definitely not petit bourgeoisie, thank you for noting that.

And what's the Gini coefficient in Georgia?